03.Instruction Set Architecture(ISA)

Instruction Set Architecture(ISA)

The “contract” between software and hardware

Functional definitionof operations, modes, and storage locations supported by hardwarePrecise descriptionof how software can invoke and access them

Strictly speaking, ISA is the architecture

Informally, architecture is also used to talk about the big picture of implementation

Better to call this

microarchitecture

Microarchitecture (微架构)

ISA specifies what hardware does, not how it does

No guarantees regarding

How operations are implemented

Which operations are fast and which are slow

Which operations take more power and which take less

These issues are determined by the microarchitecture

Microarchitecture = how hardware implements architecture

All Pentiums implement the x86 architecture

与ISA有关的内容

The Von Neumann model

Implicit(隐含) structure of all modern ISAs

Format

Length and encoding

Operations

Operand model

Where are operands(操作数) stored and how do address them?

Datatypes and operations

Control

我们用的例子: MIPS ISA

1. Von Neumann Model

Implicit model of all modern ISAs

Key:

program counter (PC)Defines total order of dynamic instructions

Next PC is PC++ unless insn says otherwise

Order and

named storagedefine computationValue flows from insn X to Y via storage A iff…

X names A as output, Y names A as input…

And Y after X in total order

Processor logically executes loop at left

Instruction execution assumed atomic

Instruction X finishes before insn X+1 starts

2. Instruction Format

Length (长度)

Fixed length(固定长度)

32 or 64 bits

Simple implementation: compute next PC using only PC

Code density

Variable length

Complex implementation

Code density

Compromise: two lengths

Example: MIPS_16

Encoding (编码)

A few simple encodings simplify decoder implementation

Complex encoding can improve code density

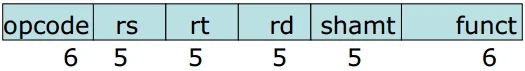

MIPS Format (指令格式)

Length

32-bits

MIPS_16: 16-bit variants of common instructions for density

Encoding

3 formats, simple encoding

Q: how many operation types can be encoded in 6-bit opcode?

R Format (寄存器类型)

e.g., add $1, $2, $3

000000

00010

00011

00001

00000

100000

alu-rr

2

3

1

zero

add/signed

注: $1 表示 1 号寄存器. 忽视 shamt.

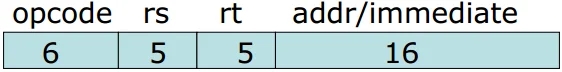

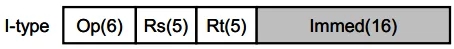

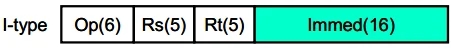

I Format (立即数类型)

All loads and stores use I-format

Assembly: lw $1, 100($2)

Machine:

100011

00010

00001

0000000001100100

lw

2

1

100 (in binary)

注: 100($2) 表示基址为 2 号寄存器, 加上 100 偏移量. lw 为 load word, 取 100($2) 地址的值, 置于 $1.

ALU ops with immediates

addi $1, $2, 100

001000 00010 00001 0000000001100100

注: [00001] <= [00010] + 0000000001100100, 即 $1 = $2 + 0000000001100100.

Conditional branches

beq $1, $2, 7

000100 00001 00010 0000 0000 0000 0111

PC = PC + (0000 0000 0000 0111 << 2)

// word offset

注: 条件跳转指令, if $1 == $2, goto 7. 7 为偏移量.

J Format (跳转类型)

Direct Jump:

opcode

addr

6

26

Jump to:

New PC = 4 MSB of PC || addr || 00

4+26+2 = 32 bits for jump target

注: MSB 为高四位(most significant bit).

3. Operations

Operation type encoded in instruction

opcodeMany types of operations

Integer arithmetic: add, sub, mul, div, mod/rem (signed/unsigned)

FP arithmetic: add, sub, mul, div, sqrt

Integer logical: and, or, xor, not, sll, srl, sra

...

What other operations might be useful?

More operation types == better ISA?

DEC VAX computer had LOTS of operation types

E.g., instruction for polynomial evaluation (no joke!)

But many of them were rarely/never used

4. Operand Model (操作数模型)

If you’re going to add, you need at least 3 operands

Two source operands, one destination operand

Question #1: Where can operands come from?

Question #2: And how are they specified?

Running example: A = B + C

Several options for answering both questions

Discuss:

Memory-Only&RegistersOptional:

Accumulator&Stack

Operand Model I: Memory Only

Memory only

Operand Model II: Accumulator

Accumulator : implicit single-element stack

注: Accumulator 相比 Memory Only, 减少了访存.

Operand Model III: Stack

Stack : top of stack (TOS) is implicit in instructions

注: Stack 相比 Accumulator, 有更多的存储单元(Acc 只有 1 个).

Operand Model IV: Registers

General - purpose registers : multiple explicit accumulators

Load - store : GPR and only loads/stores access memory

注: Registers 相比 Stack, 读写位置任意.

Operand Model: Pros and Cons

Metric I:

static code sizeNumber of instructions needed to represent program, size of each

Evaluation: memory only(1) < register(3) < load-store(4)

Metric II:

data memory trafficNumber of bytes moved to and from memory

Evaluation: load-store > register > memory only

Metric III:

instruction latencyWant low latency to execute instructions

Evaluation: load-store > register > memory only

现状: Most current ISAs are load-Store

MIPS Operand Model

MIPS is load-store

32 32-bit integer registers

Actually 31: r0 is hardwired to value 0 -> why?

32 32-bit FP registers

Can also be treated as 16 64-bit FP registers

HI, LO: destination registers for multiply/divide

Integer register conventions

Allows separate function-level compilation and fast function calls

Memory Addressing (内存寻址)

ISAs assume

“virtual” address sizeEither 32 or 64 bits

Program can name 2^32 bytes (4GB) or 2^64 bytes (16PB)

ISA point? no room for even one address in a 32-bit instruction

Addressing mode : way of specifying address

Direct: ld R1,(R2) R1=mem[R2]

Displacement: ld R1,8(R2) R1=mem[R2+8]

Indexed: ld R1,(R2,R3) R1=mem[R2+R3]

Memory-indirect: ld R1,@(R2) R1=mem[mem[R2]]

Auto-update: ld R1,8(R2) R2+=8; R1=mem[R2]

Scaled: ld R1,(R2,R3,32,8) R1=mem[R2+R3*32+8]

What high-level program idioms are these used for?

MIPS Addressing Modes: Rationality

MIPS implements only displacement

Why? Experiment on VAX (ISA with every mode) found distribution

Disp: 61%, reg-ind: 19%, scaled: 11%, mem-ind: 5%, other: 4%

80% use displacement or register indirect (=displacement 0)

How about the remain 20%?

I-type instructions: 16-bit displacement

Is 16-bits enough?

Yes! VAX experiment showed 1% accesses use displacement >16

Addressing Issue: Endian - ness

Byte Order (字节序)

Big Endian: byte 0 is 8mostsignificant bitsIBM 360/370, Motorola 68k, MIPS, SPARC, HP PA-RISC

Little Endian: byte 0 is 8leastsignificant bitsIntel 80x86, DEC Vax, DEC/Compaq Alpha

Addressing Issue: Alignment

Alignment: require that objects fall on address that is multiple of their size

32-bit integer

Aligned if address % 4 = 0 [% is symbol for “mod”]

Aligned: lw @XXXX

00Not: lw @XXXX

10

Question: what to do with unaligned accesses (uncommon case)?

Support in hardware? Makes all accesses slow

Trap to software routine? Possibility

MIPS? ISA support: unaligned access using two instructions:

lw @XXXX10 = lwl @XXXX10 / lwr @XXXX10

5. Datatypes

Datatypes

Software view: property of data

Hardware view:

data is just bits, property of operations

Hardware datatypes

Integer: 8 bits (byte), 16b (half), 32b (word), 64b (long)

IEEE754 FP: 32b (single-precision), 64b (double-precision)

Packed integer: treat 64b int as 8 8b int’s or 4 16b int’s

MIPS Datatypes (and Operations)

Datatypes: all the basic ones (byte, half, word, FP)

All integer operations read/write 32-bits

No partial dependences on registers

Only byte/half variants are load-store

lb, lb

u, lh, lhu, sb, sh

Loads sign-extend (or not) byte/half into 32-bits

Operations: all the basic ones

Signed/unsigned variants for integer arithmetic

Immediate variants for all instructions

add, addu, addi, addiu

Regularity/orthogonality: all variants available for all operationsMakes compiler’s “life” easier

6. Control

6.1 Control Instructions I

One issue: testing for conditions

Option I: Compare and branch instructions

blti $1,10,targetSimple,

– two ALUs: one for condition, one for target address

Option II: Implicit condition codes

subi $2,$1,10 // sets “negative” CCbn targetCondition codes set “for free”,

– implicit dependence is tricky

Option III: Condition registers, separate branch insns

slti $2,$1,10bnez $2,targetAdditional instructions, one ALU per, explicit dependence

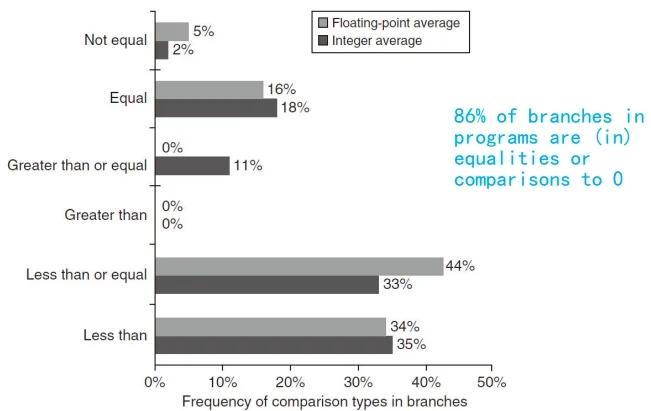

MIPS Conditional Branches

MIPS uses combination of options II and III

Compare 2 registers and branch: beq, bne

Equality and inequality only

Don’t need an adder for comparison

Compare 1 register to zero and branch: bgtz, bgez, bltz, blez

Greater/less than comparisons

Don’t need adder for comparison

Set explicit condition registers: slt, sltu, slti, sltiu, etc.

Why?

6.2 Control Instructions II

Another issue: Computing targets

Option I: PC-relative

Position-independent within procedure

Used for branches and jumps within a procedure

Option II: Absolute

Position independent outside procedure

Used for procedure calls

Option III: Indirect (target found in register)

Needed for jumping to dynamic targets

Used for returns, dynamic procedure calls, switches, ???

How far do you need to jump?

Typically not so far within a procedure (they don’t get that big)

Further from one procedure to another

MIPS Control Instructions

MIPS uses all three

PC-relative -> conditional branches:

bne, beq, blez, etc.16-bit relative offset, <0.1% branches need more

PC = PC + 4 + immediate if condition is true (else PC=PC+4)

Absolute -> unconditional jumps:

j target26-bit offset (can address 2^28 words < 2^32 -> what gives?)

Indirect -> Indirect jumps:

jr $rd

6.3 Control Instructions III

Another issue: how to support procedure calls?

We “link” (remember) address of the calling instruction + 4 (current

PC + 4) so we can return to it after the procedure

MIPS

Implicitreturn address register is$ra(=$31)Direct jump-and-link:

jal address-> $ra = PC+4; PC = address

Can then return from call with:

jr $raOr can call with indirect jump-and-link:

jalr $rd, $rs -> $rd = PC+4; PC = $rs // explicit return address registerThen return with:

jr $rd

Control习语: If - Then - Else

Understanding programs helps with architecture

Know what common programming idioms look like in assembly

Why? How can you MCCFif you don’t know what CC is?

First control idiom:

if - then - else

What's the MIPS format?

Control习语: Arithmetic For Loop

Second idiom:

for loop with arithmetic induction

RISC vs. CISC

RISC: reduced-instruction set computerCoined by P+H in early 80’s

CISC: complex-instruction set computerNot coined by anyone, term didn’t exist before “RISC”

Religious war (one of several) started in mid 1980’s

RISC (MIPS, Alpha) “won” the technology battles

CISC (IA32 = x86) “won” the commercial war

Compatibility a stronger force than anyone (but Intel) thought

Intel beat RISC at its own game … more on this soon

Intel 80x86 ISA (aka x86 or IA - 32 now)

Long history

Binary compatibility across generations <- IBM 360

1978: 8086, 16-bit, registers have dedicated uses

1980: 8087, added floating point (stack)

1982: 80286, 24-bit

1985: 80386, 32-bit, new instrs GPR almost

1989-95: 80486, Pentium, Pentium II

1997: Added MMX instructions (for graphics)

1999: Pentium III

2002: Pentium 4

2004: “Nocona” 64-bit extension (to keep up with AMD)

Intel x86: The Penultimate CISC (VAX ultimate)

Variable length instructions: 1-16 bytes

Few registers: 8 and each one has a special purpose

Multiple register sizes: 8,16,32 bit (for backward compatibility)

Accumulators for integer instrs, and stack for FP instrs

Multiple addressing modes: indirect, scaled, displacement

Register-register, memory - register insns

Condition codes

Instructions for memory stack management (push, pop)

Instructions for manipulating strings (entire loop in one instruction)

Summary: yuck!

80x86 Registers and Addressing Modes

Eight 32-bit registers (not truly general purpose)

EAX, ECX, EDX, EBX, ESP, EBP, ESI, EDI

Six 16-bit Registers for code, stack, & data

2-address ISA

One operand is both source and destination

NOT a Load/Store ISA

One operand can be in memory

80x86 Addressing Modes

Register Indirect

mem[reg]

not ESP or EBP

Base + displacement (8 or 32 bit)

mem[reg + const]

not ESP or EBP

Base + scaled index

mem[reg + (2^scale x index)]

scale = 0,1,2,3

base any GPR, index not ESP

Base + scaled index + displacement

mem[reg + (2^scale x index) + displacement]

scale = 0,1,2,3

base any GPR, index not ESP

Condition Codes

x86 ISA has condition codes

Special HW register that has values set as side effect of instruction execution

Example conditions

Zero

Negative

Example use

subi $t0, $t0, 1

bz loop

80x86 Instruction Encoding

Variable size 1-byte to 16-bytes

Jump (JE) 2-bytes

Push 1-byte

Add Immediate 5-bytes

W bit says 32-bits or 8-bits

D bit indicates direction

memory -> reg or reg -> memory

movw EBX, [EDI + 45]

movw [EDI + 45], EBX

Decoding x86 Instructions

Is a nightmare!

Instruction length is variable from 1 to 16 bytes!

Prefixes, postfixes

Crazy “formats” -> register specifiers move around

But key instructions not terrible

Yet, everything

mustwork correctly

How x86 Won Anyway

X86 won because it was the first 16-bit chip by 2 years

IBM put it into its PCs because no competing choice

Software written to x86 so x86 is the standard

Hard to complete with Intel

X86 is difficult ISA to implement

Intel can amortize(缓冲) design effort over vast salesIntel uses RISC “underneath”

Moore’s law has helped in a big way

Most engineering problems can be solved with more transistors

Last updated