09.Memory Hierarchy

Memory (Programmer’s View)

Virtual vs. Physical Memory

Programmer sees virtual memory

Can assume the memory is “infinite”

Reality: Physical memory size is much smaller than what the programmer assumes

The system (software + hardware) maps virtual memory addresses to physical memory

The system automatically manages the physical memory space transparently(透明) to the programmer

优点:

Programmer don’t need to know the physical size of memory nor manage it

A small physical memory can appear as a huge one to the programmer

Life is easier for the programmer

缺点:

More complex system software and architecture

Idealism

Instruction Supply

Pipeline (Instruction execution)

Data Supply

Zero-cycle latency

No pipeline

stallsZero-cycle latency

Infinite capacity

Perfect data flow(reg/memory dependencies)

Infinite capacity

Zero cost

Zero-cycle interconnect(operand communication)

Infinite bandwidth

Perfect control flow

Enough functional units

Zero cost

-

Zero latency compute

-

Memory in a Modern System

Ideal Memory

Zero access time (latency)

Infinite capacity

Zero cost

Infinite bandwidth (to support multiple accesses in parallel)

Ideal vs Reality

Ideal memory’s requirements oppose each other

Bigger is slower

Bigger -> Takes longer to determine the location

Faster is more expensive

Memory technology: SRAM vs. DRAM vs. Disk vs. Tape

Higher bandwidth is more expensive

Need more banks, more ports, higher frequency, or faster technology

存储技术: DRAM

Dynamic random access memory

Capacitor charge state indicates stored value

Whether the capacitor is charged or discharged indicates storage of 1 or 0

1 capacitor

1 access transistor

Capacitor leaks through the RC path

DRAM cell loses charge over time

DRAM cell needs to be refreshed

存储技术: SRAM

Static random access memory

Two cross coupled inverters store a single bit

Feedback path enables the stored value to persist in the “cell”

4 transistors for storage

2 transistors for access

注: 图为二维存储阵列. SRAM 和 DRAM 结构基本相同.

Bank Organization & Operation

1.Decode row address & drive word-lines

2.Selected bits drive bitlines

Entire row read

3.Amplify row data

4.Decode column address & select subset of row

Send to output

5.Precharge bit-lines

For next access

Static Random Access Memory

Read Sequence

address decode

drive row select

selected bit-cells drive bitlines (entire row is read together)

differential sensing and column select (data is ready)

precharge all bitlines (for next read or write)

Access latency dominated by steps 2 and 3

Cycling time dominated by steps 2, 3 and 5

step 2 proportional to 2m

step 3 and 5 proportional to 2n

Dynamic Random Access Memory

Bits stored as charges on node capacitance (non-restorative)

bit cell loses charge when read

bit cell loses charge over time

Read Sequence

1~3 same as SRAM

4.a “flip-flopping” sense amp amplifies and regenerates the bitline, data bit is mux’ed out

5 same as SRAM

Destructive reads

Charge loss over time

Refresh: A DRAM controller must periodically read each row within the allowed refresh time (10s of ms) such that charge is restored

DRAM vs. SRAM

DRAM

SRAM

Slower access (capacitor)

Faster access (no capacitor)

Higher density (1T-1C cell)

Lower density (6T cell)

Lower cost

Higher cost

Requires refresh (power, performance, circuitry)

No need for refresh

Manufacturing requires putting capacitor and logic together

Manufacturing compatible with logic process (no capacitor)

问题分析

Bigger is slower

SRAM, 512 Bytes, sub-nanosec

SRAM, KByte~MByte, ~nanosec

DRAM, Gigabyte, ~50 nanosec

Hard Disk, Terabyte, ~10 millisec

Faster is more expensive (dollars and chip area)

SRAM, < 10$ per Megabyte

DRAM, < 1$ per Megabyte

Hard Disk < 1$ per Gigabyte

These sample values scale with time

Other technologies have their place as well

Flash memory, PC-RAM, MRAM, RRAM (not mature yet)

Why Memory Hierarchy

We want both fast and large

But we cannot achieve both with a single level of memory

Idea: Have multiple levels of storage

progressively bigger and slower as the levels are farther from the processor

ensure most of the data the processor needs is kept in the fast(er) level(s)

The Memory Hierarchy

Fundamental tradeoff

Fast memory: small

Large memory: slow

Idea:

Memory hierarchyBetter Latency, cost, size, bandwidth tradeoffs

Locality

One’s recent past is a very good predictor of his/her near future.

Temporal Locality: current data or instruction that is being fetched/accessed may be needed soon.

Spatial Locality: instruction or data near to the current memory location that is being fetched, may be needed soon in the near future.

Memory Locality

A “typical” program has a lot of locality in memory references

typical programs are composed of “loops”

Temporal: A program tends to reference the same memory location many times and all within a small window of time

Spatial: A program tends to reference a cluster of memory locations at a time

instruction memory references

array/data structure references

Caching Basics

Idea: Store recently accessed data in

automatically managedfast memory (called cache)Anticipation: the data will be accessed again soon

Temporal locality principle

Recently accessed data will be again accessed in the near futureThis is what Maurice Wilkes had in mind: [Paper]

Wilkes, “

Slave Memories and Dynamic Storage Allocation,” IEEE Trans.on Electronic Computers, 1965.“The use is discussed of a fast core memory of, say 32000 words as a slave to a slower core memory of, say, one million words in such a way that in practical cases the effective access time is nearer that of the fast memory than that of the slow memory.”

Idea: Store addresses adjacent to the recently accessed one in

automatically managedfast memoryLogically divide memory into equal size blocks

Fetch to cache the accessed block in its entirety

Anticipation: nearby data will be accessed soon

Spatial locality principle

Nearby data in memory will be accessed in the near futureE.g., sequential instruction access, array traversal

This is what IBM 360/85 implemented [Product]

16 Kbyte cache with 64 byte blocks

Liptay, “

Structural aspects of the System/360 Model 85 II: the cache,” IBM Systems Journal, 1968.

Caching in a Pipelined Design

The cache needs to be tightly integrated into the pipeline

Ideally, access in 1-cycle, dependent operations do not stall

High frequency pipeline -> Cannot make the cache large

But, we want a large cache AND a pipelined design

Idea:

Cache hierarchy

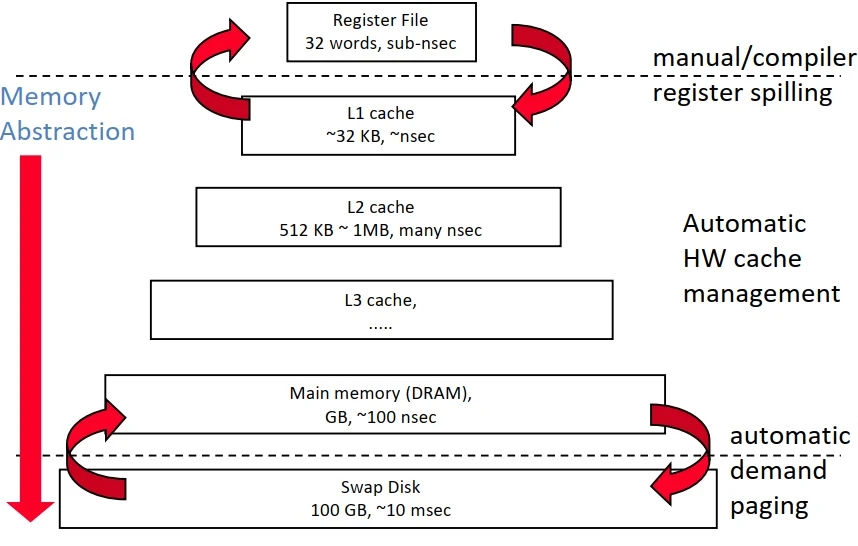

Manual vs. Automatic Management

Manual: Programmer manages data movement across

levels

too painful for programmers on substantial programs

“core” vs “drum” memory in the 50’s

still done in some embedded processors (on-chip scratch pad SRAM in lieu of a cache)

Automatic: Hardware manages data movement across levels, transparently to the programmer

++programmer’s life is easier

the average programmer doesn’t need to know about it

You don’t need to know how big the cache is and how it works to write a “correct” program!

However, what if you want a “fast” program? [Key programmer requirement]

Modern Memory Hierarchy

Hierarchical Latency Analysis

Hierarchical Latency AnalysisFor a given memory hierarchy level i it has a technology-intrinsic access time: ti, The perceived (感知的) access time Ti is longer than ti

Except for the outer-most hierarchy, when looking for a given address there is:

a chance (hit-rate hi) you “hit” and access time is ti

a chance (miss-rate mi) you “miss” and access time ti +Ti+1

hi + mi = 1

Thus:

hi and mi are defined to be the hit-rate and miss-rate of just the references that missed at Li-1

Hierarchy Design Considerations

Hierarchy Design ConsiderationsRecursive latency equation(遞歸延遲方程)

Ti = ti + mi ·Ti+1The goal: achieve desired T1 within allowed costTi ≈ ti is desirable

Keep mi low

increasing capacity Ci lowers mi, but beware of increasing ti

lower mi by smarter management (replacement::anticipate what you don’t need, prefetching::anticipate what you will need)

Keep Ti+1 low

faster lower hierarchies, but beware of increasing cost

introduce intermediate hierarchies as a compromise

Cache Basics and Operation

Cache

Generically, any structure that “memorizes” frequently used results to avoid repeating the long-latency operations required to reproduce the results from scratch

e.g. a web cache

Most commonly in the on-die context: an automatically-managed memory hierarchy based on SRAM

memorize in SRAM the most frequently accessed DRAM memory locations to avoid repeatedly paying for the DRAM access latency

Caching Basics 2

Block (line): Unit of storage in the cache

Memory is logically divided into cache blocks that map to locations in the cache

When data referenced

HIT: If in cache, use cached data instead of accessing memory

MISS: If not in cache, bring block into cache

Some important cache design decisions

Placement: where and how to place/find a block in cache?

Replacement: what data to remove to make room in cache?

Granularity of management: large, small, uniform blocks?

Write policy: what do we do about writes?

Instructions/data: Do we treat them separately?

Cache Abstraction and Metrics

Cache hit rate = (# hits) / (# hits + # misses) = (# hits) / (# accesses)

Average memory access time (AMAT) = ( hit-rate * hit-latency ) + ( miss-rate * miss-latency )

Aside: Can reducing AMAT reduce performance?

Last updated